- Home

- Marie Tillman

The Letter Page 2

The Letter Read online

Page 2

Nothing about the day seemed real except for this letter that I could touch and feel. It was both precious and awful—the last communication I’d ever have with Pat. I sat holding it for many minutes. Then I carefully opened the seal. My breath caught, and I paused another moment with my eyes closed.

I slowly flattened the letter on my lap. It had been so carefully folded. I pictured the slow, childlike way his oversized hands moved when put to a delicate task. It was one of the traits I loved most about him. The imposing exterior masking the most gentle soul. I recognized his familiar scrawl and smiled. I was ready.

I heard his voice as I read silently: “It’s difficult to summarize ten years together, my love for you, my hopes for your future, and pretend to be dead all at the same time…I simply can not put all this into words, I’m not ready, willing or able.”

The words turned my head inside out: If he couldn’t imagine dying, it must mean he was coming back alive. My heart lifted. Crazy logic overwhelmed me.

The page was a mess of ink and scribbles, of words and sentences crossed out. Rather than throw the letter away, he’d saved it, his thought process transparent. I could see his mind wrestling, and even if it wasn’t some perfect piece of prose, I liked it much better this way. Not perfect, but real.

Among the scribbling stood these sudden words:

Through the years I’ve asked a great deal of you, therefore it should surprise you little that I have another favor to ask. I ask that you live.

The tears I’d held tightly all day finally found their escape and flowed so fast I couldn’t breathe. I found myself heaving with choking sobs, my body shaking uncontrollably. Like a child, I crawled into the corner, resting my back against the walls of my bedroom to make it stop. I tucked my knees into my chest for comfort, the rest of my body curling itself into a ball. I waited for the sobs to subside but they kept coming. I didn’t want a world without Pat. I just wanted him back.

“I ask that you live.” His words burned in my head as I read them again. How could he ask this? I wondered. I don’t want to live. I want to die, I can’t do it without you, you know that, you’re the strong one, not me! I silently pleaded with him just to come back.

He knew what he was doing when he wrote those words. He knew that my instinct would be to give up, that sometimes I needed a gentle or not so gentle push. He had challenged and pushed me over the course of our relationship, seen strength in me when I sometimes didn’t see it myself.

I both cursed and thanked him, and in the end he won. As I sat huddled in the corner of my room, knees at my chin, sweatpants soaked in tears, I gave him this last request. I promised to live. I knew it would be the most difficult thing I would ever agree to do.

It was many years before I realized this final request was a gift.

Chapter Two

Pat and I had been together eleven years when he died. But since we’d grown up in the same small suburban town south of San Francisco, it seemed longer than that, like he’d somehow always been in my life. Pat’s parents, Patrick and Dannie, moved to Almaden in 1980 with four-year-old Pat and two-year-old Kevin. Dannie was pregnant with Pat’s youngest brother, Richard, during the move. My parents, Paul and Bindy, had moved to Almaden with me and my older sister, Christine, in the summer of 1979, pushed by our expanding family and drawn by the allure of sprawling tract homes, good public schools, and soccer fields in every neighborhood. We settled into our new spacious house tucked at the end of a long cul-de-sac just in time for the arrival of my brother, Paul. The new planned neighborhoods buzzed with young families, and my childhood was filled with bike riding and hide-and-seek with at least twenty other kids on our block.

Between our siblings and neighborhood sports leagues, Pat’s path and mine circled and intersected at various times throughout our childhood. When we were four, we played in the same soccer league and competed against each other. Although I don’t really remember him from then, I was vaguely aware of the rowdy, blond Tillman boys. Pat’s brother Richard played on sports teams with my brother, Paul, and ours was the kind of community where you linked everyone based on who their siblings were. You just knew who belonged with whom, which family had which brothers and sisters. By high school, we shared mutual friends and we often saw each other outside of school.

Pat was on the football team in high school and was known around campus for his cool self-confidence, apparent even in his quirky, individualist sense of style. He would wear clashing plaid shorts and tops, or T-shirts turned inside out (because he usually didn’t like what they said, I later learned, although it was always beyond me why he didn’t buy solid-colored Ts to begin with). Pat had an easy, comfortable way with the teachers and other adults around school, and I’d often see him chatting with grown-ups, completely self-possessed in a way that I wasn’t. I was painfully shy, never raising my hand in class, and terrified whenever I had to speak in front of others. If given the choice between an oral presentation or a written paper, I’d always opt for the paper, even though it meant more work. And when a speech couldn’t be avoided, I would over-prepare, write copious notes, and stand there holding them, shaking, while I spoke. But Pat had an unusual ease and presence in front of a crowd, even as a high school kid.

And that’s how I knew he had a crush on me.

The times we ran into each other in the hallways or hung out in the same group after school, he said very little to me and acted shy. And that wasn’t like him. Pat talked to everyone. There was something to the fact that he was different around me. But I was too shy to inquire further, and like most high school girls, my friends and I paid the most attention to the older boys. Girls mature faster than boys in high school, and this was certainly the case with Pat and me. But by our senior year, Pat had grown five inches and filled out to a muscular 180 pounds. While I’d always thought he was cute, I certainly noticed the difference.

Right before senior year began, a group of us played a game of capture the flag. The guys all wore camouflage, while my girlfriends and I wore shorts and T-shirts. Fueled by hormones, we chased each other around our high school campus that night, and somehow or another, Pat “captured” me. He held on to my ankle even though he didn’t really need to for the game’s rules. We sat watching the game go by, though it was hard for me to focus on anything other than the light pressure of his hand.

After that, we each let it be known that we found the other cute. Our “broker”—because every high school romance needs one—was our mutual friend Jeff, and about a month later, Pat asked me out. The night of our first date, I paced my bedroom for an hour before Pat was supposed to pick me up, getting myself more and more worked up. What should I wear? What would we talk about on the long car ride? What should I order for dinner that wouldn’t get stuck in my teeth? Frustrated, I finally picked a simple outfit of white jean shorts and a deep blue long-sleeved thermal shirt. I checked my appearance in the long mirror behind my bedroom door. The shorts were a few years old and seemed too short now, especially from the back. Well, they’d have to do, I thought as I looked at the clock.

I quickly put on lip gloss and noticed that my hand was shaking. As much as I tried to maintain a cool exterior, my insecurities bubbled to the surface. Though no one—not my sister, not my closest friends—knew, I spent most of my days and nights filled with self-doubt. On the outside, I looked put together enough; my clothes, friends, and activities all indicated that I was a normal, happy kid. But on the inside, I questioned everything I did or said.

Just then, I heard the doorbell ring downstairs. Pat had arrived.

He was down in the foyer, talking to my dad, and smiled when I reached the bottom of the stairs. I quickly said good-bye to my dad and opened the front door so we could escape the parental interrogation. I was relieved that Pat seemed nervous, too, and he sweetly opened the car door for me. He had clearly put a lot into planning our date. Among our friends, no one went out on real dates; instead we usually hung out in groups or, at most, went t

o a movie nearby. But for the occasion Pat had borrowed his dad’s car, which he stalled several times as we drove away from my house. Somehow, his effort and awkwardness put me at ease, and we talked comfortably during the rest of the thirty-mile drive to Santa Cruz.

We ate dinner at a casual restaurant on the water and talked about our mutual friends, the football game the following day, and the parties supposedly going on after the game. After dinner Pat suggested we walk down to the beach. The sun was low in the sky, and the air felt chilly coming off the ocean. We sat down in the sand shoulder to shoulder, looking out at the water as the waves crashed up on the shore. Without the formality of the restaurant, and with the daylight fading into night, our conversation became more intimate. Pat told me stories about his childhood and asked about mine. The Tillmans lived in a more rural part of Almaden where roosters crowed and wild boars roamed the streets at night. My family lived in a tract neighborhood where the only wildlife we encountered was the neighbor’s cocker spaniel. Pat’s parents encouraged him to explore the mountain trails that encircled their house, to fish along the creek, and to climb the oak trees that dotted their property. My parents always felt more comfortable when I played closer to home. They repeatedly warned me about crossing the busy intersection at the end of the street when I took trips to the drugstore to buy Lee Press-On nails and Sour Patch Kids. So while we lived only ten short minutes away from each other, our childhoods were very different.

Though nothing dramatic happened that night as Pat and I started to get to know each other—it’s not like thunder shook the earth and we both knew this was it—as I look back, it’s clear to me that our first date, as innocent as it was, started us on a path that would change both of our lives.

* * *

As Pat and I began to spend more time together, I grew to realize how completely different he was from me. What must it feel like, I wondered sometimes, not to care quite so much about what people thought? I was the “good girl,” the pleaser, always doing what I was asked. Though Pat was polite and chatty with teachers, he was always trying to see how much he could get away with. He was constantly testing boundaries, getting into trouble for usually harmless stuff, and the stories typically made me laugh. He once mooned a bus full of cheerleaders who were on their way to a football game, and another time, our junior year, he and a friend threw eggs at a group of seniors from the school roof. Pat was also one of those kids who always found a way to wander the halls during class. It seemed like every time I left class to use the restroom, there was Pat, just hanging out as if he had nowhere to be, though I have no idea how he got away with it. I couldn’t even fathom not being where I was supposed to be. I admired the way he pushed limits. His relationship with authority and the way he questioned everything was very different from what I was used to, and I was attracted to his attitude.

But when you’re the type of person who pushes limits, there will be times when you push too far. This happened to Pat only once, and the lesson learned was so powerful it stayed with him for the rest of his life. Not long after our first date, Pat got into a pretty serious fight outside a Round Table Pizza. On that night, Pat thought a friend of his was being picked on, and—always one to avenge a perceived injustice—he entered the fray with gusto, without knowing it was really the other way around. I was there but was inside sitting with my girlfriends for most of the incident. When I came out, the scene didn’t seem that bad—or even that unusual. I was used to witnessing fights, and usually they were fairly innocent and brief. This time was different. Pat had beaten a guy up pretty badly, although no one realized how badly until later.

The consequences of the fight were severe. Pat was prosecuted, had to stand trial, and was sentenced to spend time in juvenile hall after graduation. While people might have wondered why quiet, serious Marie Ugenti was hanging out with a juvenile delinquent, I had already seen that Pat was an incredibly sensitive, good guy. A lot of people, including my parents, didn’t think a juvie sentence was appropriate for a fight, which kids got into all the time. My dad had known Pat since he played Little League, and knew that he and his group were generally good kids.

Pat himself took the whole thing really seriously, though. While he didn’t talk much about the trial or his pending time in detention, he felt terrible that he’d hurt another person, and he spent a lot of time thinking about what had happened and its consequences. He started spending more time with me, and less time with friends who were prone to getting in trouble. While a lot of guys his age might have been flippant about the whole affair, Pat was not.

It’s funny to think about the early months with Pat, because our relationship then is almost unrecognizable when compared to what it became. Most of the time, we hung out in large groups of people, going to the beach or someone’s house, and I’d spend as much time talking to my girlfriends as I’d spend talking to Pat. But there were moments when I would glimpse a much deeper side of him, like when he would get sentimental about his family cat or show a tender protectiveness of his younger brothers. I soon realized that, like me, Pat had created an exterior that masked his inner self. He was much more sensitive than his cocky demeanor and bravado would suggest.

Pat’s time in juvenile hall that summer changed him. It was a lesson in adulthood and the real consequences that can result from one’s actions. As part of his punishment, Pat was supposed to do community service. The judge allowed Dannie to check him out during the day Monday through Friday and drive him to a halfway house, where he helped the staff with a variety of chores. Several times, she invited me to come along so Pat and I could spend a little time together in the car. The first time she came out of the detention center with Pat, I could tell he was trying to put on a brave face, but his eyes were red from crying and he was having a hard time composing himself. We chatted about inconsequential stuff on the way to the halfway house; then he was gone. A few days later I got a letter from him.

6-21-94

Hi dude. I apologize for taking a few days to write, there are only certain times we are allowed to. I try to work out during “activities,” which is one of the times designated for writing. I figure you would rather me come back normal and not write, than fat and write everyday. I did a little “detail” (clean-up) so they have given me time to write.

I’m sorry I was all red eyed when you came today. I handle the whole situation fine in here, but when I get in my mom’s car I get sentimental. So do not worry about me because I am fine. I am glad I got a chance to see you. Actually glad is really not the word but the less I think about it the easier it is. To tell you the truth, I can think about anything until I realize how it ties in with how much time I have left or what I can’t do.

I feel like an idiot saying that I have so much time. Some of the guys, my buddy the crank fiend I was telling you about, have years to go. So I have it easy. Back to my buddy, though, he was actually a very nice guy. Luckily I was transferred out of that unit. I really did not like it in that room. It wasn’t much bigger than this piece of paper and it was solid cement. Bear with my whining for a while, will you? I really was frustrated in there. I have never actually been in a situation where I couldn’t do anything. I was trapped. I’ll tell you the whole story later.

In my [new] unit, B7 (jail jargon), it is like a random dorm. All the beds are in one room and it has a surprisingly good atmosphere. The counselors up here are real nice in this unit. The kids are very nice too, because they haven’t seen anybody in here my size, and white, in a while. I even got a pretty good workout today. It seemed to be more of a show—the whole unit watched me. I’m sorry to be so vain but I’m very thankful they are that way. They all leave me alone and let me do my stuff.

Hopefully I will be able to write more often. Sorry for the pencil writing but it is all they allow. I figured if I wrote in cursive it would look funny so I decided to print.

It feels good to sit here and write. I guess you don’t miss something until they take it away (I’m referring to

the writing, of course). I hope this whole ordeal is over soon so I can move on from it. It is now finally getting bearable.

Tell your family that I miss them and look forward to seeing them again. I really hope you are ok. You seemed fine when I saw you today so I won’t worry. I’ve got three minutes left so I’ll wrap it up. Good bye. Hope to see you soon.

Pat

It was difficult to see Pat so emotional, but I loved getting these letters, because they gave me the chance to understand what was going on in his head. Over the past year we had started to trust each other, to slowly expose the thoughts and feelings that simmered below the surface. In Pat I found a confidant. I felt safe sharing my dreams to travel and study art, though I knew my parents would disapprove. And he realized he didn’t have to keep up his tough exterior with me. He could reveal his more sensitive, vulnerable side, and I wouldn’t laugh. Writing letters, the way we did while he was in juvenile hall, made opening up to each other even easier to do. He was struggling; he’d never been away from his family for so long before, and on top of that, it was hard for him to lose his freedom so suddenly and dramatically. In hindsight, I realize Pat’s incarceration that summer started a new phase of our relationship, one during which writing about our feelings became increasingly important. We would be separating in the fall, and letters would play a large role in the college years that followed.

* * *

During the spring of our senior year, Pat had decided to attend Arizona State on a football scholarship. I could have chosen to go with him, but I decided not to. I chose UC Santa Barbara instead. Some of my girlfriends thought I was crazy not to stay with Pat, but I took my studies very seriously and felt UCSB was the stronger school academically.

Actually, I’d been interested in schools even farther away. Each time I got a marketing packet from Duke or the University of Colorado, I’d pore over the pages, thinking about how exciting it would be to explore a part of the country so far from home. My parents were less enthusiastic about the distance, however, and made it pretty clear that wasn’t what they expected. I wanted to please them, and part of me was also a bit scared to go too far away. So in the end, I applied only to California schools and ASU. With my choice of UC Santa Barbara, I would be only four hours from Almaden—still close enough to drive home for the weekend. And I would be only a short flight away from Pat in Arizona.

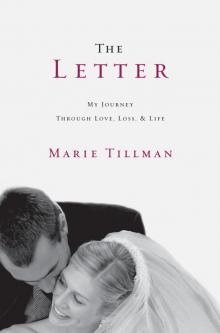

The Letter

The Letter